Calls to rename places named after historic individuals who were once idolized but are now disgraced over society’s changing views about how discrimination is bad is not unfamiliar. The anti-black racism protests worldwide have revived this mission to tear down the symbols of these people who played a part in Canada’s shameful history of discrimination and oppression.

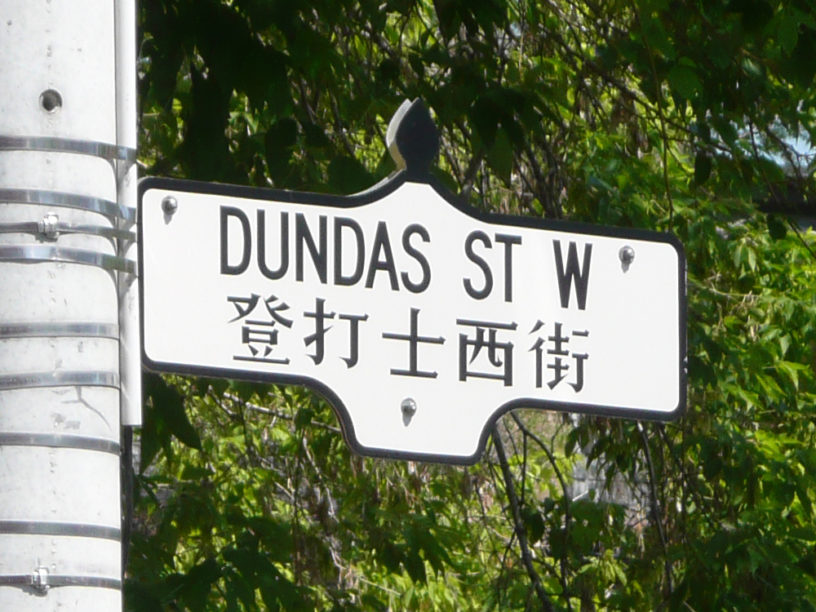

The latest of these petitions is to rename Dundas Street in Toronto. This, obviously, is not a street in Waterloo, but it’s important for everyone to participate in this discussion about what renaming a street actually means. Dundas is a major road in the donwtown core of Toronto that also lends its name to Toronto’s Yonge-Dundas Square, running east-west between Front Street and Bloor. Dundas is also a street in Hamilton, Ontario.

Dundas Street is named after Henry Dundas, a Scottish politician who served as Secretary of State for War. He was characterized as a tyrant. He played a significant role in delaying the abolition of slavery in the British Empire. He delayed it for 15 years. British historians say that even though he supported the gradual abolition of slavery, he completely opposed immediate abolition. His terrible behaviour was not even exclusive to this role. He was also impeached for the mishandling of public funds. In all accounts not only was he a terrible person, but a terrible public servant too. This is the legacy of Henry Dundas.

Henry Dundas

Rijksmuseum via Wikimedia

So, if he was so bad, why have a street named after him at all? Simply put, John Graves Simcoe, the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada from 1791-1696 who got to name a lot of places in Ontario, was friends with Dundas. Most historians agree that the only link between Dundas and Canada’s history is that he was friends with Simcoe, who actually had some significant influence in Canada.

The petition to rename Dundas Street was started by Andrew Lochhead, a Torontonian multidisciplinary artist. The reason for this petition is the belief that Toronto should condemn its association with persons who preserved systemic racism. Lochhead believes the disavowment of these individuals should not only be about tearing down statues but considering street names.

But what does renaming a street even do? For one, streets named after people are a memorial, an idolization of their legacy. Even though Canada doesn’t have slavery today, do we really want to idolize the people that played a role in it? Here’s a simple comparison: there are no Nazi statues in Germany. Germany has decided, rightfully so, to not memorialize its people who committed crimes against the Jewish peoples and minorities during the 20th century. This is a stance that nearly all people can understand and get behind. Undeniably, Hitler is a significant part of Germany’s history that needs to be discussed to educate people on genocide so that history never repeats itself, although it has. Apply the same logic to memorials of people who preserved systemic racism. Even if he did play a part in our history, which he definitely did not, doesn’t mean he should be memorialized.

Everton James, researcher of race and racism at York University, has spoken out and said that the act of renaming the street shouldn’t be performative. It needs to be combined with actual social change. Otherwise renaming a street is an empty gesture. James has recommended the representation of Black people in corporations and media as a possible start to how effective social change can be done in tandem with renaming streets.

Similar petitions have arisen about renaming schools named after John A. MacDonald who had a significant impact on Canadian history but supported residential schools, an institution responsible for the cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples. Halifax tore down a statue of its founder, Edward Cornwallis, who offered bounties for killing Indigenous peoples. There have been calls about renaming Ryerson university so it doesn’t memorialize a co-creator of residential schools.

These people, like Dundas, are not a proud part of our history. Removing the memorialization of these individuals can be an effective way to show support for the marginalized communities oppressed by the actions of these historical figures. Let me assure people that renaming institutions and tearing down statues does not erase these people from history, it only says that today, we no longer support the crimes in which they played a role. I repeat, we can and should still educate people about what these people did to recognize the consequential, but not necessarily morally right actions they did to create this country, for better or for worse, as we know it today. Renaming statues isn’t book burning. This is different.

Still, tearing down statues and renaming things without recognition of why is not perfect either. One alternative is counter-monuments. A counter-monument is a monument that challenges what the original monument said without removing the original. An example of a counter-monument is in Hamburg. There is a monument glorifying the war created by the Nazis. Instead of removing this monument, the city created a competition to design a monument that critiques the war. The winning monument was “Memorial against War and Fascism” by Alfred Hrdlicka. This maintains the conversation about war crimes and condemns the heinous crimes of the war, while still maintaining the history of how it was perceived in time. Additionally, by making it a competition, it was a successful inclusion of people into telling their own version of history.

Memorial against War and Fascism by Alfred Hrdlicka

Photo credit: Thomas Ledl via Wikimedia commons

Another alternative is the transformation of a memorial to give it context. In Belgium, a memorial to King Leopold II recognized his oppression of the Congolese peoples by removing his hand. This removal of his hand symbolizes a punishment applied to Congolese slaves during Leopold’s reign. The distortion of the monument preserves the history and art of it while recognizing the crimes against discriminated peoples. Moreover, the fact that both are still present allows there to be a vocal discussion about Beligum’s oppressive history to this day.

Obviously, both of these examples apply to statues, but can be transferred to renaming institutions and the like.

Sources:

Henry Dundas: https://nationalpost.com/news/world/who-was-henry-dundas-and-why-do-two-cities-no-longer-want-to-honour-his-memory

Petition and James: https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/statue-slavery-black-streets-1.5608652

Counter-monuments: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-august-10-2018-1.4779426/how-counter-monuments-can-solve-the-debate-over-controversial-historical-statues-1.4779446

Leopold II monument: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/feb/22/statue-missing-hand-colonial-belgium-leopold-congo

Leave a Reply