A few weeks ago, major news outlets around the world ran spectacular headlines saying, “They’ve Just Discovered Planet Nine.” This caused some people to leap for joy that the International Astronomical Union (IAU)—the body that, among other things, handles the naming of planets and natural satellites—had finally succumbed to the pressure of thousands of complaints that Pluto was still a planet and that the IAU had no right to demote it. Others rolled their eyes, pointing out that it was common knowledge that the hidden planet Nibiru was only weeks away from swinging by Earth, at which point the alien denizens of said planet would either kill us all, destroy the Earth entirely, or help humanity reach a new stage of enlightenment (depending on which constellation in the Zodiac it came from, presumably). All this new paper showed was that the government censors had gotten complacent and allowed a scientist to report the truth officially before the pre-allotted time.

Unsurprisingly, what the actual paper said is a little bit less sensational, even if it is still very exciting. The paper, titled Evidence for a Distant Giant Planet in the Solar System and published by Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown, analysed the motion of six bodies in the outer reaches of the solar system and found that those bodies had some remarkable similarities in their orbits. What they specifically found was that all the bodies were tilted relative to the ecliptic of the solar system, which is the plane that all the planets orbit on. Despite this, all six bodies came closest to the sun (a point known as perihelion) at around the same point in their orbit where they crossed the ecliptic. This result had already been noted in a 2014 paper, which tentatively suggested that the peculiar arrangement could be caused by a large planet in the outer solar system.

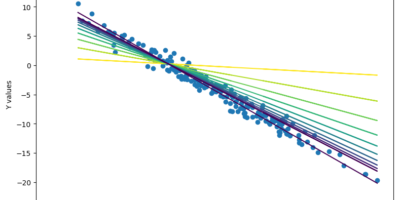

In the new paper, the astronomers noticed that not only were the perihelia all near the ecliptic, but that they were all orientated in the same direction, meaning that from the sun’s perspective all of the perihelia would be scattered about one point in one region of the sky, in line with the known planets. The researchers calculated that this particular alignment had only a 0.007% change of happening by chance, and so set out to determine if an unknown planet could force these results. Using a variety of simulations, they narrowed in on a planet with an orbital period of 15,000 years and a mass of 5-10 Earth masses, making it a Neptune-sized gas giant. Its closest approach would be seven times further from the sun than Neptune. This planet would also need to have its orbit anti-aligned with the objects it shepherds, so its perihelion would be on the opposite side of the sun to the perihelia of the aforementioned six bodies.

Some scientists have celebrated the finding as rigorous, while others question it. Planetary Scientist Dave Jewitt, for instance, points out that the paper eliminates dozens of other bodies in similar orbits to the six studies since they don’t have the interesting perihelion alignment. This calls the 0.007% chance of coincidence into question, and Jewitt worries that “a single new object that is not in the group would destroy the whole edifice.” There is a precedent for mathematical predictions being used to hypothesize unseen bodies in the solar system. Most notably, in 1846, Urbain Le Verrie predicted an unseen planet was causing the known irregularities in Uranus’ orbit. When astronomers at the Berlin Observatory received word of Verrie’s work, they found Neptune almost exactly where he had predicted it after only one night of searching.

The paper has also caused a cornucopia of jokes that this new planet is coming to replace Pluto. These are caused in large part by the fact that one of the paper’s authors, Mark Brown, has greatly relished (and even been a primary perpetuator of) his reputation as “the man who killed Pluto”; Brown’s discovery of dwarf planet Eris was an influential piece of evidence in showing that Pluto was not a particularly special body, and instead was one of many mid-sized bodies that orbited beyond Neptune.

Many questions still remain about the possible existence of Planet Nine. For one, current models of planet formation do not allow for a large planet to form so far away from the sun. A controversial explanation is suggested in the discussion at the end of the paper: this planet formed with the other gas giants, was kicked out of the inner solar system by Jupiter or Saturn, and then found a stable orbit in the outer solar system by slowing down in the presence of copious gas hypothesized to be pervasive in the very-early stages of the solar system’s formation.

A definitive answer may be forthcoming about the existence of the Planet Nine. The researchers are already using the Japanese Subaru Telescope in Hawaii to survey the sky where they most expect it to be (opposite its perihelion, since objects both move slower and have longer to travel the further away they are from the object they orbit). Of course, even if it is not found there still could be other planets out there. And until it is positively identified in a telescope, Planet Nine remains nothing but an interesting and potentially well-supported hypothesis.

Leave a Reply